The new British Newspaper Archive (BNA) was launched a couple of months ago, publishing (at the time of writing) 3 million pages of historical newspapers from 144 different publications. Given the importance of the press in the period and the methodological difficulties when working with it today, the publication of the BNA is a major achievement and marks a significant event in nineteenth-century studies.

Shortly after its launch, Bob Nicholson, who blogs at the digital victorianist published an excellent review of the resource, as well as a thorough critique of its pros and cons. Since then, Bob has added a couple of further posts, exploring some of the points in his review (here and here). For a full description of the BNA and an introduction to the context in which it has been published, I recommend you take a look at Bob’s review; below, I’ll offer a few observations of my own.

As Bob notes, the BNA must be situated alongside the British Library’s decision to close its newspaper library at Colindale, shifting most of its holdings to their site at Boston Spa. Although not the most welcoming of ‘interfaces’, the buildings at Colindale facilitated a variety of users, including students and scholars, genealogists, and those using the collections to revisit the newspapers of their past. This new resource, it must be assumed, stands in for the physical buildings and it’s holdings. If the purpose of Colindale was to allow readers to locate and read articles from the nineteenth-century press, then this resource easily surpasses the existing facilities. But of course, there is much more to Colindale that simply the provision of articles: there is all the material in the building not represented in the resource; there are the things you can only appreciate from looking at the printed copy (and even more that can only be realized by comparison between digital and print); there is a wealth of reference material on the shelves; and sometimes it is only by browsing pages, one after the other, that you realize what is you are looking for. This resource offers its digitized page images and transcripts as surrogates for the printed copies housed at Colindale, but really it offers something entirely different.

What is clear from the BNA is that it is not a resource aimed at academic researchers. The interface is relatively cluttered, foregrounding things such as the premium print service (“from only £39.95”) and free example pages recording famous events from history, neither of which are of much interest to those who know the period. Nor is it a resource aimed at those interested in the press more generally (although such users will find it indispensable). The BNA is designed to encourage as many users as possible to access articles with the minimum of fuss, and it achieves this very well. Of course, given that the user is charged per article view this makes commercial sense, but the effort to open up the press beyond the (still relatively small) community of academic researchers is, of course, to be welcomed. There is some contextual information to help users understand what it is they are reading. Clicking on the small ‘i’ by the publication title opens up a brief description of the newspaper that will be of interest to experts and newcomers alike (my thanks to Ed King for bringing this to my attention). At present this information is a little patchy – perhaps understandably given the size of the resource – and mostly only extends to a couple of paragraphs. However, given the neglect of the press, especially that outside London, these snippets, when considered together, are a very helpful compilation of information about the press. It is a shame that they are not searchable (as far as I can tell), and they, like the articles, are only available for reading, one by one.

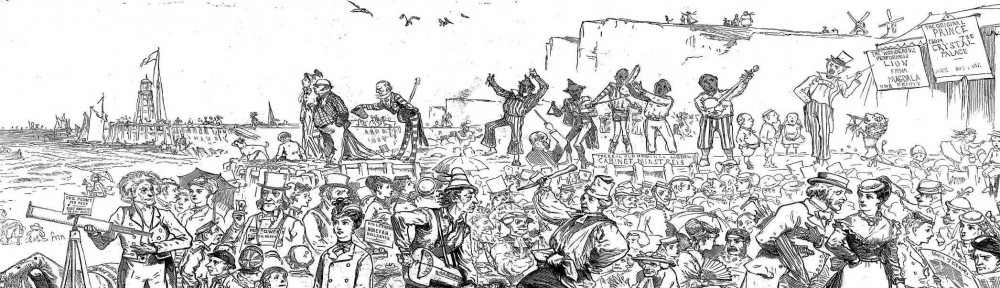

One of the challenges of digitizing historical newspapers is the scale of the resulting data set. Given the sheer amount of print represented by a run of newspapers, it rapidly becomes very costly to carry out extensive editorial work. Brightsolid, like ProQuest and Gale before them, have opted to concentrate on search as a mode of access, designing a metadata schema to facilitate this process. From the home page the user is offered the chance to search for some text. The hits (and there are likely to be many, even with the various filters) are presented in groups of ten. One major problem here is the way in which the user scrolls through the pages of hits. Although the user can jump to the first or last page, and those before and after the page he or she is on, it is impossible to jump to anywhere else. If you are browsing a run of issues, it would take you something like 240 clicks to get to an issue ten years into the run. Each hit is presented with a thumbnail of the page and a snippet of the textual transcript. It is on the basis of this information that the user must make his or her choice and, given that page views are metered, this is not a casual decision. A click on a hit will open a page viewer that allows the user to move around the page and scroll in or out. This interface is fluid and intuitive, probably the best executed aspect of the resource and by far the best example of its type. The decision to offer the user the page rather than article nicely foregrounds context and, as I’ve argued elsewhere, simply providing page facsimiles helps users to understand many different aspects of nineteenth-century print culture. However, at no stage is there any information about things like page size, price, important textual divisions, or anything else about the newspaper. The user is asked to choose a hit (and pay for it) purely on the basis of the few words, taken from an uncorrected transcript, that they can see.

Given the commercial model of this resource, the emphasis on breadth over depth is understandable. This resource banks on users finding lots of relevant hits and then spending credits or time, depending on the subscription package selected, sifting through them. It is notable, though, how much user activity is commodified by the resource. When looking at pages from newspapers, users can do the following:

- print

- download

- bookmark

- tag

- comment

- buy print

The first two options are fairly generic and the third, the creation of personal bookmarks, quite common in similar resources. The option to buy prints makes explicit the commercial ends of the resource. The remaining two options, however, are a little more interesing. The addition of tags and comments allow users to annotate the content, improving the resource for others. These, along with the option to correct the OCR-generated transcripts, constitute an admirable commitment to crowdsourced information by Brightsolid. The size of most runs of nineteenth-century newspapers means that crowdsourcing is really the only way to create reliable edited resources. The question, of course, is whether users will be willing to provide their time and expertise freely to improve an explicitly commercial product. Unlike, say, Wikipedia, this labour will be locked behind a paywall rather than contributing to a resource that feels like it is owned by a community of users. I suspect Brightsolid and the British Library looked at the success of the pioneering Australian Newspapers Online, now available via the portal Trove, for an example of crowdsourced OCR correction. The difference, though, is that the Australian resource is publicly-funded and free to access. Users are helping to improve their cultural heritage for all, not for a select group of paying users or to improve profits for a bunch of shareholders.

Brightsolid are not alone in allowing their users to work on and improve their products. ProQuest have long encouraged users to tag content and Gale Cengage’s forthcoming Nineteenth-Century Collections Online (NCCO) features a range of crowdsourcing options. Time will tell whether users will contribute sufficient material to make this worthwhile. While I would be happy to contribute my time and expertise freely for a resource that was free to use, I am very reluctant to lock up my contributions so that someone else can make money from them. Mind you, I’m aware that this describes much of academic publishing too, but that’s another story.

The BNA demonstrates what happens to our cultural heritage when there is no political will for public investment. The nineteenth-century newspaper press was one of the period’s greatest achievements but, rather than celebrate it, opening it up and giving it back to the nation, the British Library have been forced to sell it off. This is not just a gripe over having to pay for access to what is already public property, although this is obviously important; rather it is a lament over the opportunity lost through this compromise. Brightsolid have done a good job with this resource and I suspect that it will be a commercial success. However, as a model of funding digitization projects it is a disaster. Firstly, to become commercially sustainable one set of users have been privileged over all others. While this is not a bad thing (opening up the nineteenth-century press to a wider audience can only be a good thing!), it restricts what I, as a media historian and teacher, can do. Bob’s post is good on this, but I can’t stress enough how short-sighted it is to finance a resource that is currently impossible to use in the classroom.

This leads me to my second point: the way Brightsolid have digitized this material also restricts possible uses. This is a resource for finding articles, not reading newspapers, and this is done by Brightsolid’s search engine and database on the user’s behalf. There is no scope here for data mining, for analysis of textual transcripts, or for the interrogation of metadata. This actually runs counter to the dominant trend within both the digital humanities and commercial digital publishing, making BNA seem a little old fashioned. Gale Cengage’s NCCO, for instance, allows users to carry out rudimentary data mining. This is no mere moan about the way the project was executed. Taking advantage of the digital properties of digitized materials is the way in which we learn new things about them. Locking the data away means that users are stuck with old methodologies, treating the articles as if they were printed paper even though they clearly aren’t.

Perhaps most importantly, the resource restricts reuse through its implementation and explicitly forbids it in its (admirably clear) terms and conditions:

You can only use the website for your own personal non-commercial use e.g. to research newspaper archives and other archives featured on the website that you are interested in and to purchase goods that we may sell on the website. We are also happy for you to help out other people by telling them about the newspaper archives and other information available on the website and how and where they can be found. However, you must not provide them with copies of any of the newspapers (either an original image of the newspapers or the information on the results page), even if you provide them for free.

So, not only are you forbidden from sharing facsimiles of material out of copyright, but you are also forbidden from using content for commercial ends. Instead of a publicly-funded resource, open to many more users and many more uses, sparking off innovative pieces of research and entrepreneurial commercial activity, the British Library have locked up a key piece of our cultural heritage so that Brightsolid can make money selling access to interested users. There is no chance for any of this content to enter digital culture, becoming recontextualized as it interacts with other content; instead, it is trapped within the interface, pretending that it is paper, so users can read articles, one after the other. On these terms, it must be said, the BNA is excellent (and let me repeat, the page viewer is one of the best I have seen); but as a resource that contributes to the UK economy, scholarship, or even one that helps us learn more about nineteenth-century print culture, it is limited. One can only hope that the British Library does not now consider this material ‘done’, It is essential that they recognize that this is one possible implementation, one possible representation of this content amongst many others, and so should be open to other uses of the data – whether transcripts, page images, or metadata – that might come along in the future.

[N.B. Corrected paragraph about contextual information 10 January 2012]