[On the 17 March 2012 I gave this as a talk at the London Nineteenth-Century Studies Seminar at the Institute of English Studies, Senate House. It’s quite long, so I’m going to blog the talk in five parts. More Great Expectations pace than Our Mutual Friend, hopefully…]

Part 1: Introduction

The quotation – ‘Scarers in Print’ – comes from Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. In Boffin’s Bower, the Golden Dustman, Noddy Boffin, listens to Silas Wegg, one-legged ballad-seller and sometime runner of errands. Boffin, the retired servant of a recently deceased, rich, miserly dust contractor called Harmon, wants someone to read to him in the evenings and Wegg, who Dickens describes as an ‘igneous sharper’ on account of his wooden appearance and wily ways, is more than happy to oblige – at twice the proffered rate.1 Boffin wants what he calls an opening into print, but the revelation of the contents of the book, which turns out to be Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, startles him. The narrator tells us:

Mr Wegg, having read on by rote and attached as few ideas as possible to the text, came out of the encounter fresh; but, Mr Boffin, who had soon laid down his unfinished pipe, and had ever since sat intently staring with his eyes and mind at the confounding enormities of the Romans, was so severely punished that he could hardly wish his literary friend Good-night, and articulate “Tomorrow.”2

Here, the action of Silas Wegg transforms the book from one thing – a smart set of volumes, ‘red and gold. Purple ribbon in every wollume, to keep the place where you leave off’3 – into something quite different. For Boffin, Wegg has performed some sort of arcane rite, unlocking the contents of the book while, at the same time, bestowing it with depth so that it becomes a container.

Boffin is struck by this transformation of object into archive, turning the book into a repository, in a way that Wegg, who reads on by rote and dwells not on what he reads, does not. Boffin thinks this is because of Wegg’s worldliness

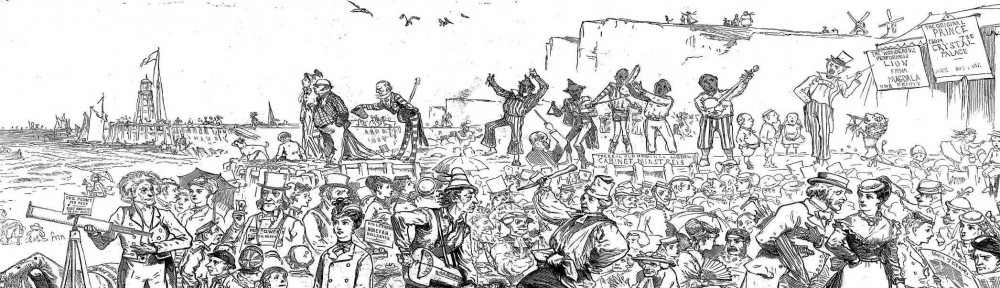

‘Commodious,’ gasped Mr Boffin, staring at the moon, after letting Wegg out at the gate and fastening it: ‘Commodious fights in that wild-beast-show, seven hundred and thirty-five times, in one character only! As if that wasn’t stunning enough, a hundred lions is turned into the same wild-beast-show all at once! As if that wasn’t stunning enough, Commodious, in another character, kills ’em all off in a hundred goes! As if that wasn’t stunning enough, Vittle-us (and well named too) eats six millions’ worth, English money, in seven months! Wegg takes it easy, but upon-my-soul to a old bird like myself these are scarers. And even now that Commodious is strangled, I don’t see a way to our bettering ourselves.’ Mr Boffin added as he turned his pensive steps towards the Bower and shook his head, ‘I didn’t think this morning there was half so many Scarers in Print. But I’m in for it now!’4

The scarers here are ghosts, conjured out from the archive by the apparently magical process of reading. However, the scarers are not in the book, but are produced through overlapping sets of technology put to work in a particular social configuration. The technology of writing creates a decipherable code that can be transposed without deformation from one material context to another. In this instance, the code is inscribed onto the printed pages of the book; but to become meaningful the book must be opened, there must be light to see, and there must be a reading mind able to process the information produced by the eyes. But there is even more here. Wegg’s mind processes what he reads and his vocal chords (mellowed with gin and water) articulate his translation of the marks on the page as sound. These utterances are, in turn, received by Boffin’s ear, which detects the vibrations in the air. His mind processes this information, separating Boffin’s voice from the other sounds in the room and isolating the spoken signs from one another as comprehensible units. This mental reckoning is not divorced from bodily reaction, and what Boffin hears affects his body, giving rise to sensation that provokes further articulation.

As Walter Ong reminds us, the scene of communication is always complex, taking place in the company of both speaker and listener, writer and reader (even if the latter is imagined), and depending on a range of learned competencies, technologies, and material. Yet in Orality and Literacy, Ong is suspicious of analyses that foreground media as they suggest ‘communicaiton is a pipeline transfer of units of material called “information” from one place to another.’5 As Ong makes clear over the course of the book, he recognizes the constitutive role material media play in enabling communication, but he argues that focusing upon these risks neglecting the necessarily intersubjective nature of human communication. However, I want to follow the lead of people like Friedrich Kittler and try and explore what happens to material media in acts of reading and writing.6 Literacy rests on doing things with things: in these posts, I want to explore what happens to those things during the production of text.

These posts explore whether Mr Boffin is right. Taking Boffin’s impression that there are ‘Scarers in Print’, I consider both the apparently uncanny nature of textual content as well as its putative location in print. Is content really ghost-like? And in what ways is it imagined as being within media? My argument is that reading involves learning to ignore (or at least unconsciously process) the material media necessary to permit text to be in the world. This is not, of course exceptional, but happens all the time, whenever a piece of text attracts a glance. The industrializtion of print in the early nineteenth century led to the proliferation of text upon a wider range of surfaces. The effect was to emphasize the promiscuity of text while lending it presence. The same words appeared in lots of places and appeared in the same fashion, reifying themselves as objects, while occluding more of the material world by bringing it into textual discourse. There had never been so many texts, and they had never been so dispersed. The result, I argue, is an unprecedented opportunity for objects to misbehave, to assert their agency in unexpected ways.

There are four posts to come. The first explores the role of materiality in media more thoroughly, arguing that shifts in material presence underpin the practice of reading. Although literacy is usually described as a cognitive process, deciphering signs inscribed in written code, it necessitates interactions with objects of various kinds. Rather than understand these interactions as secondary, I argue that they are the condition of reading. The second turns to Our Mutual Friend, offering the novel as an explication of the agency of material. If, as Ong argues, writing is predicated upon an economy of death and resurrection, then this novel – published in parts, featuring characters who play parts, and, in the case of Wegg, become alienated from their parts – reminds us that this economy is based on material media. The third turns to the present, and applies this analysis to the digital objects that enable textuality today. If the nineteenth-century archive betrays a concern about keeping things in line, then the web, the largest, most ill-disciplined archive we have ever created, permits new material possibilities. Taking Facebook as an example, I demonstrate how a different technology of inscription – a set of networked servers and a carefully designed software architecture – create different conditions of reading and writing. As Facebook forces us to live with alienated ghosts from our pasts, we are reminded of both the central role that material plays in literacy, as well as the potential for objects to exert themselves against their prescribed passivity as media. The final post offers some conclusions. While I argue that we need to remember both objects and what we do with them when we think about literacy, recognition of the reflexivity of these process tends to be bit alarmist. Looking briefly at this history, I nevertheless stress that in disciplining the material world by making it legible, we too are disciplined.

Notes