Part Three: Being Moved

As they sustain relationships, objects become enmeshed in the emotional lives of those they bring together. For Marx, commodity fetsishism meant that objects mediated social relations, taking on a fantastical form that then became naturalised. According to Thomas Richards, this is the reason that descriptions of commodity culture tend to produce accounts ‘of a fantastic realm in which things think, act, speak, rise, fall, fly, evolve.’1 All objects, in this view, can become social actors, but it is those that directly address us, that have been inscribed in some way and are perceived to pass on some sort of message, that interest me here. Mediating objects, according to Derrida, create the sender and receiver, the you and the me, as they move between people. The telepathic connections they activate promise a touch across time and space. Touching always involves touching back: as these media interpellate, they demand a response of some kind, creating the conditions for reciprocity. These things move because they are moving things.

In the first issue of Household Words, Dickens and his subeditor William Henry Wills provide an account of a visit to the General Post-Office at St Martin’s-le-Grand. ‘Valentine’s Day at the Post Office is supposed to be one of Household Word’s romances of the everyday, where the souls of the ‘mightier inventions of the age’ are revealed to the reader.2 The General Post-Office is the ‘mighty heart of the postal system of this country’ (12), distributing letters around London, the rest of the country, and across the empire. While the article celebrates the achievements of the postal service, with a heavy dose of human interest, it returns obsessively to the issue of theft. The Post-Office, it transpires, blames the public for using the post to send money, especially coins. ‘The temptation’, they write, ‘it throws in the way of sorters, carriers, and other humble employés is greater than they ought to be subjected to’ (10). At the end of the article, Dickens and Wills return to this theme, noting the dimmed glass window installed, panopticon-like, through which the sorters might be watched. They remark that it ‘is a deplorable thing that such a place of observation should be necessary; but it is hardly less deplorable […] that the public, now possessed of such conveniences for remitting money […] should lightly throw temptation in the way of these clerks, by enclosing actual coin’ (12). By 1850 the post office was understood as a closed communications system: the invention of the penny post, the use of envelopes, and the Post Office Scandal of 1844 buttressed the understanding of the postal system as a set of private channels between sender and receiver. The insistence on the senders’ guilt for tempting the clerks, responds to uncertainty about the conditions of this privacy. Coins are particularly troublesome, as they can be felt through the envelopes, rendering them transparent. There is an uneasiness here about the hands through which letters must pass: hands that fondle and caress the bodies of the moving things that convey content from one place to another.

These mentions of theft come either side of the description of the Dead-Letter Office. The place where undeliverable letters are sent, the Dead-Letter office fascinates Dickens and Wills as a place where wealth accumulates. For Derrida, destinerrance means that all letters can become dead letters, as all letters can activate any number of multiple connections and so summon up all sorts of people. Yet, as John Durham Peters notes, the letters in the Dead-Letter Office are dead precisely because they have no chance of interception. These are bodies that have been interred (the word repository also means a tomb) and so have stopped moving. The Dead-Letter Office is a necessary corollary to the emergent role of the postal system in the broader information economy, serving as a material supplement to the disembodied content moved from place to place. As Durham Peters argues, the ‘need for it to exist at all is an everlasting monument to the fact that communication cannot escape embodiment and there is no such thing as a pure sign on the model of angels.’3 As Durham Peters puts it, this is not a problem of the rupture of minds, but of bodies. It is a problem of erotics.

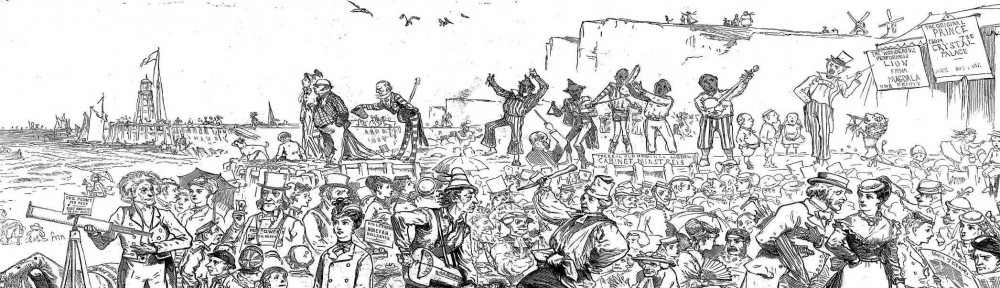

Detail from front page of Mugby Junction, All the Year Round, 16 (1866), 1. From Dickens Journals Online (DJO) (2012-) http://www.djo.org.uk/.

The analogy with the serial form of Household Words and All the Year Round is clear. Dickens, as Steven Connor has argued, also set out to haunt the homes of his readers, not least by circulating his words into their households. As a Christmas number, Mugby Junction is both part of the weekly series of All the Year Round and also distinct. Its distinctness – it is twice as large (and expensive) and has its own pagination sequence – allows it to better suit Christmas and also serves to situate it in the annual series of Christmas numbers. Mugby Junction, then, haunts the fireside at Christmas, filling the holiday period; but it also, as a supplement, haunts the weekly series, reminding readers that there are other rhythms in play – and, of course, that these, too, have their own print forms.

What is odd about Mugby Junction is that the narrative of Barbox Brother’s decision is the second in the series, not the last. ‘Barbox Brothers and Co.’ tells of Barbox Brothers’s trip to the ‘great ingenious town,’ Birmingham, where he stumbles across a lost girl called Polly (10). This turns out to be an elaborate sting operation by his ex-lover, who wants Barbox Brother’s forgiveness. Dickens uses the two girls to rejuvenate Barbox Brothers and open him up to the influence of others (this is Dickens after all). After Barbox Brothers forgives his ex-lover and her husband, he becomes Barbox Borthers and Co, taking, and I quote ‘thousands of partners into the solitary firm’ (16). Barbox’s Brothers’s Birmingham experience reconciles him to his past, transforming him from the ‘Gentleman for Nowhere’, as he is known at Mugby Junction, into the ‘Gentleman for Somewhere’. He decides not to move on and instead takes a house in Mugby. No longer haunted, Barbox is no longer compelled to haunt and so makes his haunt his home.

Detail from ‘Main Line. The Boy at Mugby.’, Mugby Junction, All the Year Round, 16 (1866), p. 17. From Dickens Journals Online (DJO) (2012-)

Open-ended serials like newspapers and periodicals also negotiate these two potential ends. As frequentative media, there is always the potential that they become too stuck, like Barbox Brothers, in repetition; but, in constantly chasing novelty, there is also the danger that they will break free from the structure set out in advance and, so, like Barbox Brothers at the conclusion of his story, become something else. Like the Freudian death drive and pleasure principle, eros and thanatos, each of these possible ends has its own motive force. The skillful editor carefully balances these two drives, creating a kind of perpetual present, issue after issue. In narrative, it is only at the end that the beginning and the middle can be conceived as a whole, but then you have to start again with another. Newspapers and periodicals also employ this constant changing of the subject to drive readers on from article to article, issue to issue, volume to volume. However, an editor is not, really, a narrator, and all they can offer is a precarious middle from which the reader can survey the past (represented by the neat sequence of back issues) and the future, tantalizingly out of reach but reassuringly expected to be much the same. This middle, a present teetering between the past and future it produces, is itself intended to pass. As print genres predicated on not finishing, newspapers and periodicals enable repetition while ensuring progression, ordering both past and future by allocating each a period and numbering it accordingly. Moving on by staying put, the next issue displaces the previous, a temporal change enacted spatially. Barbox Brothers might reach his happy end, but the stories keep coming nonetheless.

1Thomas Richards, The Commodity Culture of Victorian England (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990), p. 11. [back]

2Anonymous [Charles Dickens and William Henry Wills], ‘Valentine’s Day at the Post Office’, Household Words, 1 (1850), 6-12. [back]

3John Durham Peters, Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 169. [back]

4Steven Connor, ‘Dickens, The Haunting Man (On L-iterature)’, conference paper given at A Man for all Media: The Popularity of Dickens 1902-2002, Institute for English Studies, 25-7 July 2002. Available here. [back]