Moving Things

What is interesting about Dickens’s ‘A Preliminary Word’ is that it is not really preliminary. It appears as the first article in the first issue of Household Words, rather than in some sort of supplementary or preliminary space. The same is true of the notice that declares, unequivocally, that Household Words will end. In neither case are these pieces outside of the sequence of articles that constitute each issue; nor are they in some sort of space outside of the numbered sequence of issues. Serials such as periodicals and newspapers have a troubled relationship with beginnings and endings. Even if they announce their commencement or mark their demise within their contents, their form still posits a series that precedes the first issue and could continue beyond the last. The first issue of Household Words might declare it as first in two of the sequences in which it performs – the issue and the volume number – but the date places it in a temporal sequence that both precedes and extends beyond them. Now, there is no number prior to this one but, nonetheless, no issue of a serial, even the first one, exists in isolation. Just as the date indicates a virtual prehistory for the serial, its combination of typographical features also suggest how these fictional predecessors might have looked. Had they existed, the actual first issue suggests, they would also have had the same masthead, the two columns, the same range and tone of articles, and be made of the same size paper cut into the same number of pages. Equally, Dickens’s final note might declare the end of Household Words at issue 479 at the end of volume 19, but we can, nonetheless, imagine number 480.

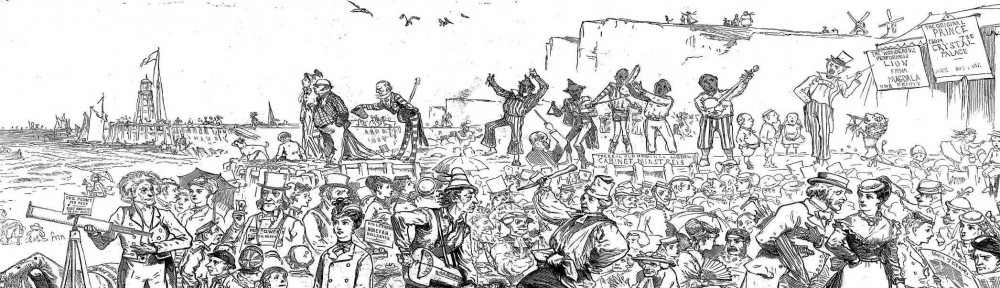

Household Words, 19 (1859), p. 620. From Dickens Journals Online (DJO) (2012-) www.djo.org.uk.

Repetition establishes an abstract structure that surpasses any particular issue, regardless of its place in the series. Simply by indicating that they are serials, individual issues of periodicals and newspapers summon up this broader structure. All nineteenth-century printed objects associated themselves with a genre so that readers could tell, in advance, what it was that they were looking at. Newspapers and periodicals also signalled where they belonged in this wider print ecology, identifying themselves both as newspapers or periodicals and a particular type of newspaper or periodical. As miscellanies, newspapers and periodicals also printed a wide range of textual genres, the selection often going some way to indicate the type of periodical or newspaper a particular publication considered itself to be. However, the open-ended seriality that defines these print genres also causes a further genre effect. In this post, I argue that it is this particular type of genre effect that allows periodicals and, especially, newspapers, to structure the emerging definition of information in the period.

Genres are commonly used for classification, helping to allocate instances of something to a particular class and then, usually, mapping a genealogy. However, as I’ve posted previously (see, for instance, ‘The Matter with Media’ and ‘Parsing Passing Events’), Carolyn Miller’s definition of genre as ‘social action’ usefully takes us beyond the classificatory. For Miller, ‘a rhetorically sound definition of genre must be centred not on the substance or form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish.’1 This is genre as situational and pragmatic, helping people to negotiate new situations and achieve their respective ends. Now, nineteenth-century newspapers and periodicals served a number of purposes, both for producers and consumers, but all parties had a stake in this underlying virtual form. The dynamic of seriality entailed a sort of contract: publishers attempted to anticipate the demands of their readers by giving them more of what they had already demonstrated they wanted; readers repeatedly spent their money on the understanding that they would not be disappointed. Each issue of a periodical or newspaper responded to a particular moment, orienting content towards the perceived interests of its readers, while resurrecting forms from the past to assert its underlying identity. In this way, the abstract identity of the periodical, imperfectly manifested in each individual issue, was a negotiated, consensual structure into which new content could be accommodated and made familiar. Every new issue was already attuned to this structure, and the repetition of (predominantly formal) features reaffirmed its presence.

Front pages of first four issues of Household Words. Household Words, 1 (1850), pp. 1, 25, 49, 73. From Dickens Journals Online (DJO) (2012-) www.djo.org.uk.

As miscellenies, nineteenth-century periodicals and newspapers had a tendency towards fragmentation: the virtual structures that I’m trying to describe, partially manifested in each issue, asserted a centripetal force that countered this tendency and asserted the identity of the publication between issues. As no two issues were the same, these virtual structures evolved over time, allowing periodicals to shift their identity according to the vicissitudes of the market. Although virtual, these genre forms had real agency and social meaning, structuring the specific material forms of individual issues and lending presence to the broader publications of which they were a part. They also constituted an interpretive structure that preceded individual issues and articles, determining in advance how they might be understood. The printed newspaper or periodical, issue after issue, invoked a perfect medium – perfect because virtual – that promised to organize and make legible the complexities of everyday life. Yet it is the effect of seriality that I want to stress here. The repetition of the generic features that signalled continuity helped the reader to differentiate between mediating form and the mediated content: those features that were repeated, issue to issue, were associated with the mediating form, and so discarded, while those that differed were associated with the content. Commercial products of the industrialised press, newspapers and periodicals enacted a process where immaterial content was produced through formal repetition.

In this way, newspapers and periodicals played a part in the emerging and increasingly dominant understanding of information in the period. Just as information was being defined as an immaterial commodity, able to be communicated without deformation, the press appeared to offer a way of structuring information, granting it both material form and social presence. Many scholars have identified the nineteenth century as the period where the modern concept of information was consolidated. This was information as self-evident, immaterial, portable, reproducible and able to reside in any form of media without deformation. The discursive foundations for this understanding of information were established in the eighteenth century, but it was with the demands of industrial capital that information came into its own. A number of information-gathering initiatives by the state – the census, civil registration, income tax – were complemented by the development of elaborate bureaucracies as companies struggled to manage their works. Beyond the developing civil service, the largest were in the post office and railway companies, organizations that specialized in moving things. In George Eliot and Blackmail, Alexander Welsh claims that the value of information lies in its moment of use, so there was an imperative to store it up and make it ready for recall.2 As the value of information is difficult to judge in advance, it exerts material pressures of storage and management. The industrial age was built on paperwork and the resultant bureaucracies were a frequent source of satire, not least for Dickens. Information might be pure spirit, allowing power to operate at a distance, but it depends on doing things with paper, and so is always in a way fallen. Novelists, engaged in paperwork of their own, were particularly attuned to the potential for paperwork to fail, for the crucial document to be misplaced, or the body of paper to take on a life of its own and exert itself, like Krook’s shop or Harmon’s mounds, against those that would seek to master it.

Unauthored, and so without origins, information only exists as mediated. In a paper from 2002, Steven Connor associates the period’s interest in patterns of recurrence – evident in the development of statistics, evolutionary theory, and the management of time in industrial production – to the growth in mass media.3 Connor opposes the frequentative to the singular; the recurrent, which keeps taking us back, and the event that marks a break and so moves us on. The iterability of information – its conditions of storage, reproducibility and recall – mean that it belongs to this frequentative mode. As serials, periodicals and newspapers, too, are frequentative, mediating difference through repetition. The newspaper, in particular, was linked to the emerging informational culture. For Welsh, the ‘newspaper was the institution that above all made the people of the nineteenth century aware of information and communication.’4 For Richard Terdiman, newspapers became the ‘most characteristic informational and commercial institution of the nineteenth century.’5 However, as information transcends the contingent forms that give it substance, the material form of the newspaper only partially accounts for its role in this economy. It is when the newspaper – or, to a lesser extent, the periodical – is in action, when readers encounter these recurrent forms over time, that they can produce and circulate information. Readers might read newspapers and periodicals one article, page, or issue at a time, but they nonetheless invoke the larger abstract generic forms that give these smaller components meaning. These abstract forms, which are always prior to any act of reading, mark content as that which changes and, in many cases, indicate its derivation beyond the page. In this way, content becomes liberated from a complex set of recurrent formal structures, allowing information to flow.

1Carolyn Miller, ‘Genre as Social Action’, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70 (1984), 151–167. [back]

2Alexander Welsh, George Eliot and Blackmail (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 44. [back]

3Steven Connor, ‘Dickens: The Haunting Man’ (presented at the A Man for All Media: The Popularity of Dickens, 1902-2002, Institute of English Studies, 2002). Available here. The published version is ‘Dickens, The Haunting Man’, Literature Compass, 1 (2003), 1–12. Available here (£). [back]

4Welsh, p. 52. [back]

5Richard Terdiman, Discourse / Counter Discourse: The Theory and Practice of Symbolic Resistance (Cornell University Press, 1985), p. 119.

[back]

Pingback: 5 Intriguing Things: Wednesday, 1/22 – Alexis C. Madrigal – One Business – One Business

Pingback: The (anti?)Stream | Actuary Lit

Pingback: Mobilya ofis buro | 5 Intriguing Things: Wednesday, 1/22