[this is my contribution to a panel called Victorian Archival Mediations at the NAVSA 2019 conference in Columbus Ohio. The panel was organised by Matthew Poland and our fellow contributors were Ann Garascia and Anna Wager]

In M.R. James’s short story ‘Casting the Runes’, first published in More Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1911), two men are haunted, one after the other. Each is the victim of a man called Karswell, who is disgruntled because nobody takes seriously his research into the occult. The first, John Harrington, was killed in 1889 when Karswell cast the runes upon him because of a bad review of his book. The focus of the story, however, is on the second, Edward Dunning, on whom Karswell cast the runes because he recently rejected one of his papers. While trying to work out what is happening to him, Dunning meets John Harrington’s brother, Henry, who tells him about when he and John first found the runes.

I suppose the door blew open, though I didn’t notice it: at any rate a gust – a warm gust it was – came quite suddenly between us, took the paper and blew it straight into the fire: it was light, thin paper, and flared and went up the chimney in a single ash.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘You can’t give it back now.’1

You can’t give it back now, says Henry to his brother just after the runes go up in smoke. Written on light and thin paper, this is material that wants to be destroyed, that resists becoming part of the record. Ephemera is alive in ‘Casting the Runes’ but wishes for its demise. Ephemera belong to the dead.

* * *

There is something special about unexpectedly finding a piece of ephemera, tucked away, perhaps, in the leaves of a book. In what follows I want to consider why the unexpected survival of ephemera has the power to move us. Rediscovering something that we have chosen to keep but have since forgotten evokes powerful and complex feelings: not only do such mementos allow us to relive the moment so fully, but they surprise us by their capacity to do so. Something of this underpins the way we experience all encounters with ephemera when we happen to find it. Regardless of who preserved it or why, chancing upon such material strikes us so because it reminds us of all that we have chosen to forget.

‘Casting the Runes’, however, warns us about such pleasures. Not only are the runes themselves ephemeral, seeking their own destruction, but the haunted receive warnings that take ephemeral forms. Surviving when it should have been destroyed, there is something of the grave about ephemera. We keep such things because we want to remember and we recognise that such timely objects remain anchored in the moment even when that moment has gone. Yet in choosing to keep some things and not others we acknowledge that we cannot keep it all. In ‘Casting the Runes’ the ephemeral is a threat to the well-ordered world of the archive and its gatekeepers. Ephemera stand for the transient, the modern, and the abundant, all of which threaten institutionalised memory. In the end the gatekeepers triumph: Karswell is killed by the runes, and so history is preserved against the overwhelmingly ephemeral. Yet the custodians of this archive remain haunted, aware of what they do not collect and aware, too, of the other histories that such material might preserve. The persistence of ephemera charms us because it takes us back, but it does so by undermining the past as we think we know it.

* * *

‘Casting the Runes’ is probably the best-known story about the dangers of peer review in English literature. In many ways it is quite typical of M.R. James. As in most of his other stories, it concerns a group of men, most of whom live alone and are more comfortable in homosocial, scholarly communities; and, as in most of his other tales, the supernatural threat comes when they stray out into the world. In an often embarassingly literal return of the repressed, James’s scholars and anitquaries usually become haunted when they disturb some ancient relic, struggling against their supernatural assailant until they escape back to the safety of museum or quad. In ‘Casting the Runes’ there is no relic and those haunted are already out in the world, yet it too is about policing boundaries, about expelling or escaping what is provoked when curiosity strays too far.

The story focuses on Edward Dunning. On the way back from the British Museum, where he has been doing some research in the reading room, he notices an advertisement in the tram window that reads ‘In Memory of John Harrington, FSA, of the Laurels, Ashbrooke. Died Sept. 18th 1889. Three months were allowed’ (150). This ominous warning is followed by another a couple of days later when he is given a leaflet on which he glimpses the name ‘Harrington’ before it is twitched out of his hands (153). Later, in the Select Manuscript Room, Dunning is just about to leave when a man taps him on the shoulder and hands him some papers he had left behind. ‘May I give you this?’, the man says, ‘I think it should be yours’ (153). Dunning thanks him and takes the papers; on his way out he asks the staff who the man was and learns that his name is Karswell.

Returning home Dunning finds himself out-of-sorts, as if ‘something ill-defined and impalpable had stepped in between him and his fellow men’ (154). A sleepless night follows, including a disturbing moment when, reaching beneath his pillow, he finds, ‘a mouth, with teeth, and with hair about it’ (155). Seeking company Dunning meets the Secretary who, in turn, introduces him to John Harrington’s brother, Henry. Henry Harrington tells Dunning that, before he died, John had also run into Karswell and had subsequently experienced a similar feeling of oppression. John was a keen concert goer and, on looking around for his programme, had one handed to him; on later inspection, it was found to contain ‘a strip of paper with some very odd writing on it in red and black’, which, as we know promptly went up in smoke (158). Two things later came in the post for John: a Bewick woodcut of a man being pursued by a demon, and a calendar with the pages after 18 September 1889, torn out.

They realise that Dunning, too, has three months to live and the rest of the story follows Dunning and Harrington as they try and escape the curse. Finding the runes amongst Dunning’s papers (and stopping them disappearing out the window) they hatch a plan to return them to Karswell. Shortly before the day Dunning is due to die they learn Karswell is to travel to France and so plan to board the train with him. After a tense journey they manage to slip Karswell the runes in his ticket wallet just as the train reaches Dover. As Karswell boards the ferry a crewman remarks that he thought he saw someone following him. The next they hear Karswell is dead.

* * *

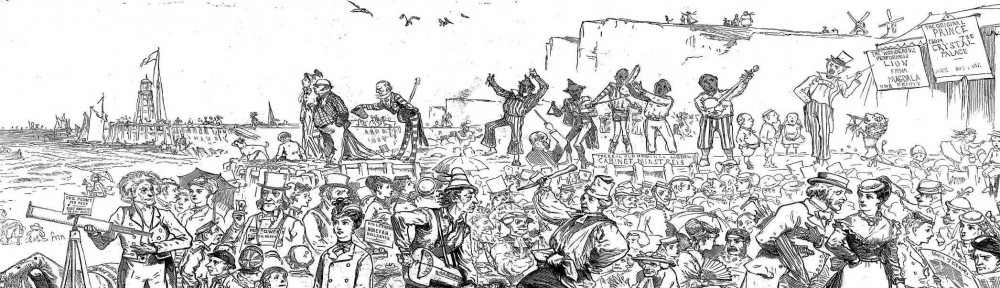

So far, so uncanny. The narrative tension in ‘Casting the Runes’ comes because Dunning knows when he will die, his life revealed to be plotted for him in advance. However, my interest is in the role of ephemera in all of this. Not only are the warnings of impending death carried by ephemeral objects – advertisements, leaflets, scraps, calendars – but the runes, with their propensity for self destruction, are ephemeral too. The story was published in 1911 and set sometime after the turn of the century so it demands the longest of nineteenth centuries to be discussed here. With its first murder in 1889, however, and its focus on the British Museum, it deals with how the Victorian archive was set against a modern world characterised by abundance, temporal compression, and the onward rush of modernity. Susan Zieger calls ephemera ‘facilitators of ephemerality’: when we look at such objects we move from evocations of temporality, moments in time, to the technology that makes time pass.2

The story distinguishes between the acceptable study of the occult by disinterested scholars and its enthusiastic pursuit by those such as Karswell who believe in what they research. It then maps these two approaches, the disciplined and ill-disciplined, onto distinct media economies. While Karswell can research in the British Museum, Harrington’s hostile review means that his work will only be admitted to mark the boundary of what is acceptable leaving him with just ephemeral scraps. The Museum here represents the archive as a place of ordered knowledge preserved for all time; Karswell instead becomes a peculiar representative of modernity, identified with the contingent, the transient, and the supplementary. As Priti Joshi and Susan Zieger have noted, ephemera are constituted by their exclusion from the archive and so haunt it, marking the deficiencies of institutional collections and so becoming more authentic witnesses to the past as a result. However, as they also note, the archive, too, haunts the ephemeral, either dooming the it to extinction outside the archive’s walls or extinguishing the its ephemerality by subjecting it to institutional discipline within.3

With the British Museum at its heart, James’s story dramatises these narratives of inclusion and exclusion. However, by identifying the ephemeral with the occult it insists on its impending annhiliation, the expected fate that makes it ephemeral. We are used to thinking of the contents of the archive as the remains of a process of institutionalised forgetting. The matter that structures our lived experience of the present is too vast, too complex, to be preserved in entirety and so instead we make just a portion available for future recollection. Monuments to the discarded, ephemera often find their way into the archive as part of this process. But ephemera are designed to pass. It is when they survive despite themselves – the ticket stub in the book; the annotation in a margin – that they have the ability to evoke the rest.

The forgotten can only be evoked as an absence, however. Susan Stewart’s definition of the souvenir provides a useful explanation for the powerful feelings that ephemera can prompt. For Stewart the souvenir is both of the moment and stands for it: metonym and metaphor, it offers the possibility of authentic connection to a moment passed, but, in its partiality, creates a space for narrative. Stewart argues that the power of the souvenir comes through its impoverishment, its failure to bring back the moment in its entirety creating instead that desire for origins we call nostalgia.4 Ephemera make such good souvenirs because they belong to the fabric of what was. Ephemera, as mentioned above, belongs to the dead.

‘Casting the Runes’ sides with Dunning and Harrington against Karswell, ultimately upholding the values of the archive against ill-disciplined ephemera. However, by making Karswell the victim of his own occult machinations, the story recognises the efficacy of his practices even as it expels them from the narrative. Indeed, by passing the runes to Karswell Dunning and Harrington embrace the logic of ephemerality. Slipped inside programmes, papers, and a ticket wallet, the runes are always accidental survivors and, as each of these things have been left behind in the story, the runes are also associated with the discarded or forgotten. Each time the runes are exchanged from one person to another there is contact: they are, then, transitive and transactional, connecting people together for a moment before passing away. And as the runes themselves are indecipherable, they have no other meaning than the action they accomplish, which is to perish.

To pass on and to be passed on, to receive the runes is to die. When they persist, ephemera are so compelling because they offer a glimpse of the richness of the present that has passed. Yet they cannot bring it back: even our own souvenirs fall short, leaving a gap that we fill with nostalgic desire. What the runes remind us is not that we will die but that we, too, will become part of the unrecoverable past. The archive serves to reassure us that memory is safe in other hands while the ego tricks us into thinking we persist, in all our richness, from one moment to the next. Marked as disposable and so part of the technology that allows the world to move on, ephemera remind us of what we have forgotten: that the past as lived was immeasurably richer than we remember it and that we, too, will be diminished when recalled.

This is not as bleak as it sounds and the story suggests how we might read the runes aright. On the one hand ‘Casting the Runes’ suggests there is comfort in bachelor life, in the archive and its proper use, and it distrusts what lies outside: women, sex, modernity. But as always in M.R. James this comfortable world is haunted by what it excludes. Karswell works in the reading room alongside Dunning; museum collections contain ephemera too. We are all going to die, but until then, the story suggests, we should keep the runes in motion. What we feel when we find something tucked away in a book, surviving despite itself, is a reminder that to remember we have to forget. Keeping the runes in motion allows us to see that what we remember, and what we forget, depends upon what we choose to keep.

1 M.R.James, ‘Casting the Runes’, Collected Ghost Stories, edited by Darryl Jones (Oxford: Oxford Worlds Classics, 2011), pp. 145-164 (p. 158). [back]

2 Susan Zieger, The Mediated Mind: Affect, Ephemera, and Consumerism (NY: Fordham University Press, 2018), p. 3. [back]

3 Priti Joshi and Susan Zieger, ‘Ephemera and Ephemerality’, Amodern, 7 (2017) available here. [back]

4 Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 1993), pp. 135-6. [back]